The Psychology of Weird Fiction

Reflections on weird fiction from a perspective of Kleinian object relations theory.

In the foreword to my collection of weird horror stories, No One Came For Me, I allude to a specific psychological theory concerning the primal nature of existential dread. As it pertains to weird fiction especially, perhaps some of you would find it interesting to venture deeper into that maze. This text is for you.

The great thinker Melanie Klein, working in that hazy twilight that occupies the borderland between psychology and philosophy, builds her theory on the – in my view intuitively convincing – premise that the first subjective experience of a new consciousness (i.e. that of a very small infant) is chaotic and incomprehensible. The inner life of a newborn is an incessant stream of unfamiliar perceptions and sensations with no fixed point or frame of reference. Initial consciousness is content without interpretation.

The “objects” of object relations theory are the psychic objects that are gradually conglomerated from these chaotic perceptions, by way of the foundational meaning-making function of the psyche. According to object relations theory, even the adult psyche understands the world through psychic objects, but with the development of the psyche as we age, we learn to understand much more complex objects and object relations. In fact, the first objects are so primal that it can be difficult for the Kleinian student to grasp the concept. But let us try. Consider that certain perceptions in the life of a newborn tend to appear together with some regularity – the infant does not understand that it is hungry, but it perceives the discomfort of that hunger; the infant does not understand breastfeeding, but its mind coalesces a psychic object out of the perception of its mother’s breast against its mouth and the associated perceptions such as tasting the milk and feeling the alleviation of discomfort. Thus, the first, primal interpretations are made by the developing psyche. However, according to Klein, even though the infant psyche has learned to comprehend crude objects, it cannot yet comprehend the more abstract relationship between them – and thus, hunger is not yet interpreted as the absence of the contentedness that comes from nourishment, but felt as the presence of something undesirable – an evil object.

And then, over time, the infant experiences again and again that the evil object (for instance, hunger) and the corresponding good object (for instance, satisfaction from feeding) never coexist. This adds a higher level of interpretation of the mass of perceptions that used to be absolute chaos: the good object has the power to drive away the evil object – and some time after the good object withdraws, the evil object returns to terrorize the psyche. Meanwhile, as the chaos increasingly takes on order, the objects themselves are becoming increasingly more complex. The primal psychic object that grew out of the experience of breastfeeding evolves to become identified with the breast itself, which is not just an experience but a phenomenon with a coherent appearance, regular extensions in space, which is then found to be consistently associated with the even more complex object of the Mother, and so on. However, Klein holds that the psyche at this time has still not developed the capacity to integrate good and evil objects, and therefore, when Mother is doing something desirable (such as feeding the hungry infant or providing soothing stimuli such as rocking or singing), she is interpreted as a good Mother-object, but when she is doing something undesirable (such as yelling or – like the original evil object that caused the discomfort of hunger – not being there), she is interpreted as an evil Mother-object, whose relation to the good object is that she is its opposite, its evil counterpart. The psyche wants to have the good objects around forever, and to destroy the evil objects forever – who wouldn’t? But note that all of this happens very early in the infant’s development – object permanence is not yet a feature of the psyche, meaning that each time the evil object goes away, the psyche believes that it has successfully destroyed it. But, terribly, the evil object somehow keeps returning from destruction, a formidable foe indeed.

Thus, at this time the psyche interprets the world from the viewpoint that it is at the center of eternal ongoing conflicts between good, protective objects and evil, persecuting objects. Klein refers to this as the schizo-paranoid position. “Schizo-”, meaning “split”, refers to the inability of the psyche to comprehend that the good and evil objects it perceives are in fact different aspects of one and the same external phenomenon, instead splitting them into good and evil polarities. “Paranoid” obviously refers to the unpleasant experience of being in a situation where evil forces keep appearing from out of the shadows to assault you. Most importantly, Klein’s choice of the word “position” rather than “stage” or “phase” is a deliberate attempt to emphasize that this interpretation of the world is not a primitive mode of functioning that is then outgrown and replaced by a higher function, but rather, a viewpoint of the psyche that remains latent within us all even after the second Kleinian position is developed. According to Klein, even the mind of a a perfectly well-adjusted and high-functioning adult could, under the “right” circumstances, regress to functioning from the schizo-paranoid position – and when that happens, it manifests to the outside observer as a psychotic episode.

It is the schizo-paranoid position which is of most relevance to us as weird fiction enthusiasts, but for those curious, the second Kleinian position is termed the depressive position, and it emerges on the scene of the psyche as soon as the infant develops the capacity to integrate the good and bad objects – with object permanence, the psyche finally comprehends that the good object and the evil object are one. It is named after depression because with this comprehension comes two realizations that, if not resolved in the sense that one learns to endure them, lead to depressive functioning: the realization that all the impulses and efforts of the psyche to destroy the evil object, have been equally directed at the good object, which gives rise to guilt; and the realization that the evil object can never be defeated because it is inextricably intertwined with the good object, which gives rise to despair. “The world is a place of evil and I am myself evil” as a motto of depression. Klein feels that seeing the world from the depressive position is the highest functioning any of us can hope for, i.e. there is no “third position” beyond this integration of good and evil objects.

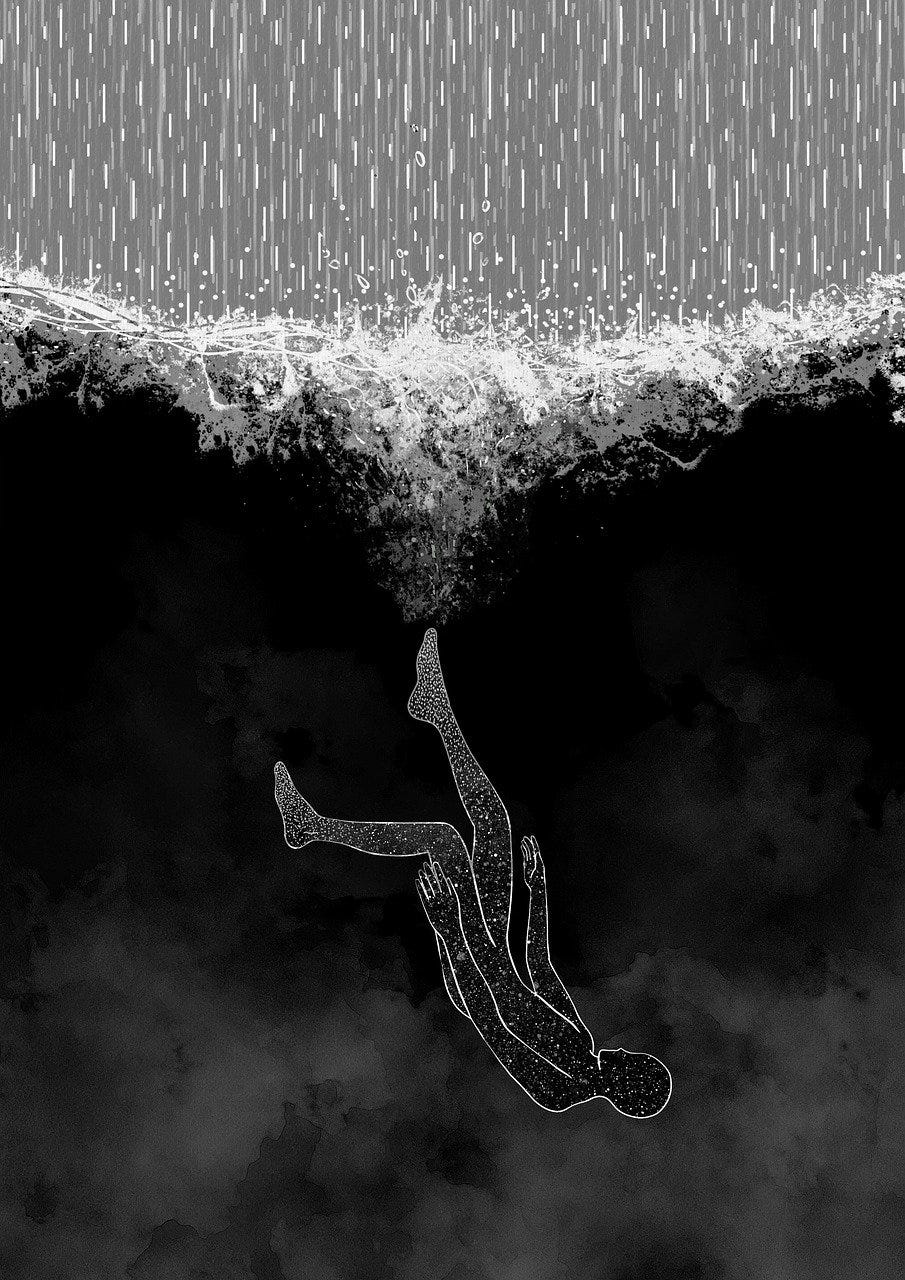

So what does this all have to do with weird fiction? (Hands up everyone who did not read this far without once thinking of Coraline?) What fascinates me is the preverbal nature of Kleinian schizo-paranoid dread. I can only speak for myself, but weird horror frightens me more deeply than (what shall we call it?) ordinary horror, so much more deeply in fact that I fail to convey it in words. This is also one of if not the common element of weird fiction – the attempt to transcend the constraints of language to evoke “the nameless dread” and countless similar phrases. I contend that Klein is right, and that the nameless dread is so much more than a literary trope, it is the dark waters we were all born out of. Leviathan is not tamed, psychic development is not ascending a ladder step by step – it is growing layer upon layer of bark on top of a core of chaos that is still there. The world around you and me is chaos, and while our minds may filter that chaos into the comprehensible (albeit depressing) structure that we consciously experience, that conscious experience is nothing but a tuft of foam at the tip of a wave on a deep ocean of unconscious processes, at the bottom of which reality dissolves into a terrifying, schizo-paranoid maelstrom of dissociated and incomprehensible fragments of endless perception.

Why do some of us enjoy weird fiction? Why do some sailors gaze down at the depths of the sea? The schizo-paranoid position is always lingering right there in our psyche as a potential alternate organizing principle for a dissolving world; perhaps some of us remember what waits for us there, beyond language. Perhaps we like to keep an eye on it.

Interesting! I’ve never heard of Klein, and the ideas are great to chew on. But I do have some notes.

A babies senses are still developing long after their born. Rather than being dropped in the icy waters of stimuli, it’s more like the slow turning up of a volume dial— starting in the womb.

The hunger example is off too, because the negative feeling of hunger is not the absence of contentedness. It’s a hormone sent by the pituitary to encourage eating, and is in fact an ‘evil feeling’. And the feeling of being content after (or while) eating are completely different stimuli, and they can coexist— or else we’d never eat more than we need.

Similarly the baby is not creating a psychic object when being breastfed, it’s being classical conditioned. Removal of negative stimulus (hunger) reinforces behaviour (breastfeeding). And the baby only knows to suck the nipple through reflex. All of the supposed ‘good’ and ‘bad’ objects are similar stimuli for directing behaviour. There is no interpretation or psyche involved, only the simple mechanics of lower order intelligence —(but this does make me wonder if ‘good’ and ‘bad’ simply stem from the desire to maximise positive stimuli and reduce negative ones?). It’s like Skinner’s caged rats. They sit in a box and are shocked until they press a button, or they press a button and get fed. They can do nothing more than to learn to press the button through random chance.

The first creation of psychic objects would likely be object permanence, which is the first example of being able to keep something in mind—Even a mother’s face is recognised as patterned stimuli up until that point and reactions are classically conditioned.

Also the idea of learning that the evil object and the good object being one and the same causing despair isn’t the root cause because they’re not equal. Reinforcement (good object) is more effective than punishment (bad), so it’s still a worthwhile trade. Though it’s true that despair is caused by perceiving an issue as insurmountable.

But seeing the depressive position as the highest attainment is silly, as is the ‘nameless dread’ being innate. ‘Nameless dread’ is simply fear born out of ego. The feeling that you’re not special, that you’re incapable, that you’re wrong, and of course despair caused by an issue perceived to be insurmountable. I would say it’s born during Erikson’s Trust Vs Mistrust developmental phase, specifically in those who follow the ‘mistrust’ path (which we all undergo to some level)— to trust your environment, you under some form of ego death, and to mistrust it is rely entirely on yourself— your ego, which is fallible. I’d also say that’s why it resonates with certain demographics so well (Introverts love weird fiction, and introverts rely on themselves more, so are more sensitive to feelings of despair). Weird fiction tends to contend with the idea of us vs them just on a higher level— usually cosmically. But if you have no ego and don’t consider those things as ‘other’, you can’t be frightened by them, as they pose no threat.

P.S. I shouldn’t have written this while I’m so sleepy, hope it’s not all bad! Definitely loved the article!